Singapore’s economic outlook is looking a bit rocky as weak external demand is being exacerbated by a number of factors.

Lackluster local economic indicators, tightening monetary policies globally and a languid China are all contributing to the city-state’s poor outlook.

“More signs are pointing to a potential contraction in Singapore’s [gross domestic product] in the second quarter of 2023, where several key leading economic indicators have deteriorated further in the month of April,” Kelvin Wong said in a note last week.

Wong is the senior market analyst for the Asia Pacific region for broker OANDA.

In April, the Singapore Institute of Purchasing & Materials Management purchasing managers’ index declined to 49.7 from 49.9 in March. This is below the 50-point neutral mark, where anything under denotes contraction and anything above expansion.

This was also the second month of contraction.

The electronics sector sub-component which represented 47% of Singapore’s industrial output remained in negative territory for the ninth consecutive month at 49.2, Wong pointed out.

Meanwhile, Singapore’s non-oil domestic exports saw a decline of 9.8% year-on-year in April, compared to a 8.3% contraction in March. This was worse than consensus estimates of a 9.4% fall, Wong noted.

This follows city-state’s first quarter GDP print which showed that the Singapore economy was keeping its head just above water. Singapore’s GDP grew 0.1% year-on-year in the first three months of 2023. This was a major slowdown from an annual increase of 2.1% in fourth quarter 2022.

“These observations suggest that global economic growth is in a slowdown mode after major developed nations’ central banks embark on a tightening monetary policy stance in the past year that sucked out prior excessive global liquidity conditions,” Wong said.

Turning towards China, which is one of Singapore’s largest trading partners, Wong said it is clear that the first quarter growth spurt from the “post-Covid zero reopening” episode has dissipated.

In the first quarter of this year, China’s GDP jumped 4.5% year-on-year, beating forecasts, and was up 2.2% quarter-on-quarter. This was thanks to China ending most of its Covid-19 restrictions, after implementing some of the world’s strictest controls for around three years.

This spurt is now showing signs of slowing, with its manufacturing PMI falling below the 50-point mark to 49.2 in April.

This slowdown may lead to a deflationary spiral in China, Wong said, which would hurt countries that export goods and services to the world’s second largest economy, with Singapore being one of them.

“The Chinese central bank, the People’s Bank of China needs to switch away from its current conservative stance to loosen its liquidity tap further to stimulate growth,” Wong said, adding that the PBoC is still in a “wait and see” approach to its monetary policy stance.

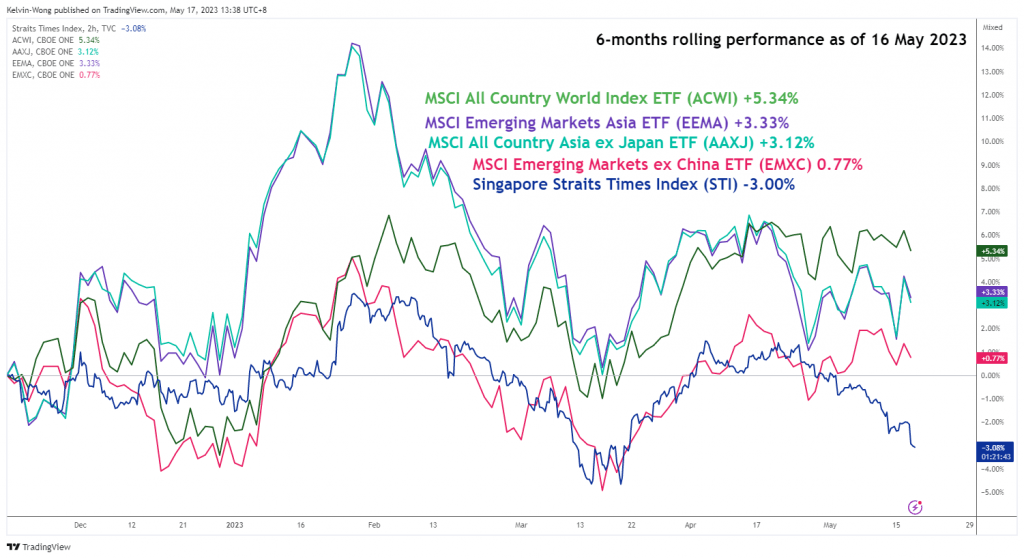

On the equities front, Singapore’s Straits Times Index has been struggling.

The benchmark index has underperformed against global equities as well as its neighbours in the region, as illustrated by the image below:

“Hence, if China’s domestic demand continues to falter in the coming months without a more aggressive accommodative monetary policy stance from PBoC, Singapore’s STI may continue to see further potential downside pressure in the second half of 2023,” Wong said.

Looking at which sectors will be hurt most by the slowdown in China, Wong said in an interview with Diplomatic Network (Asia):

“The manufacturing sector will be the primary one to watch for the ripple adverse effect from China and weak external demand due to its direct exposure,” Wong said.

“The next sector will be the banking sector as it is impacted by a secondary following-through impact via the heightened risk of a technical recession that may occur in second quarter 2023 which in turn lead to a lesser demand for loans and higher provision for delinquent loans being set aside in banks’ balance sheets.”

Singapore is not alone, however, with most of Southeast Asia’s economies being tied to China’s.

“Most ASEAN economies are dependable on external demand for growth either exports or tourism. Given the current lackluster external demand environment coupled with China’s growth slowing down post-reopening, the ASEAN economies are likely to face downside pressure in the near to medium-term term,” Wong said.

For now, however, ASEAN economic indicators show that the region is doing fine.

On which sectors could provide investors with some opportunities, Wong was not very optimistic.

“In the near to medium term, most sectors are likely to see downside pressure. Growth may come from defensive sectors such as utilities and infrastructure,” he said.