Cambodia is on the precipice of graduating from its status as a “least developed country”, according to Asia Development Bank, after a decade of solid growth has improved its economic and social development standing.

The term “least developed country” is used by international organisations, such as the United Nations and the World Bank, to classify countries with the lowest levels of socio-economic development.

LDCs are low-income countries which are faced with severe structural impediments to sustainable development, according to a UN definition, and are highly vulnerable to economic and environmental shocks.

For a country to graduate from LDC status, it must meet various criteria set out by the UN. There is however no clear ‘next level’ after graduating from LDC status.

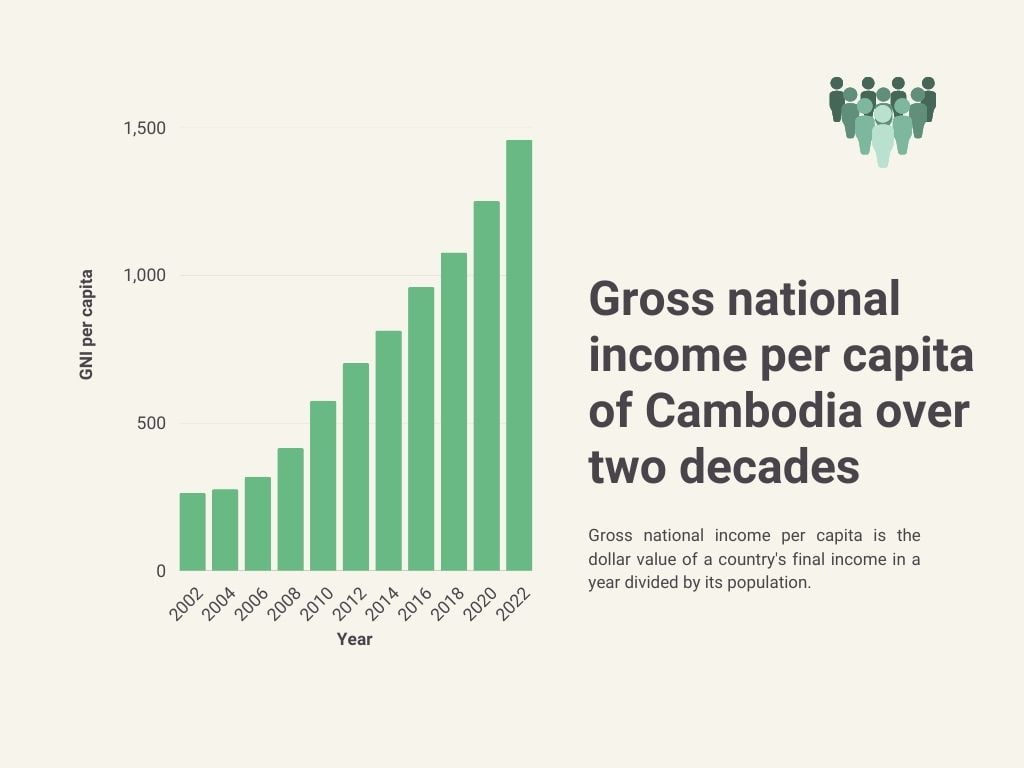

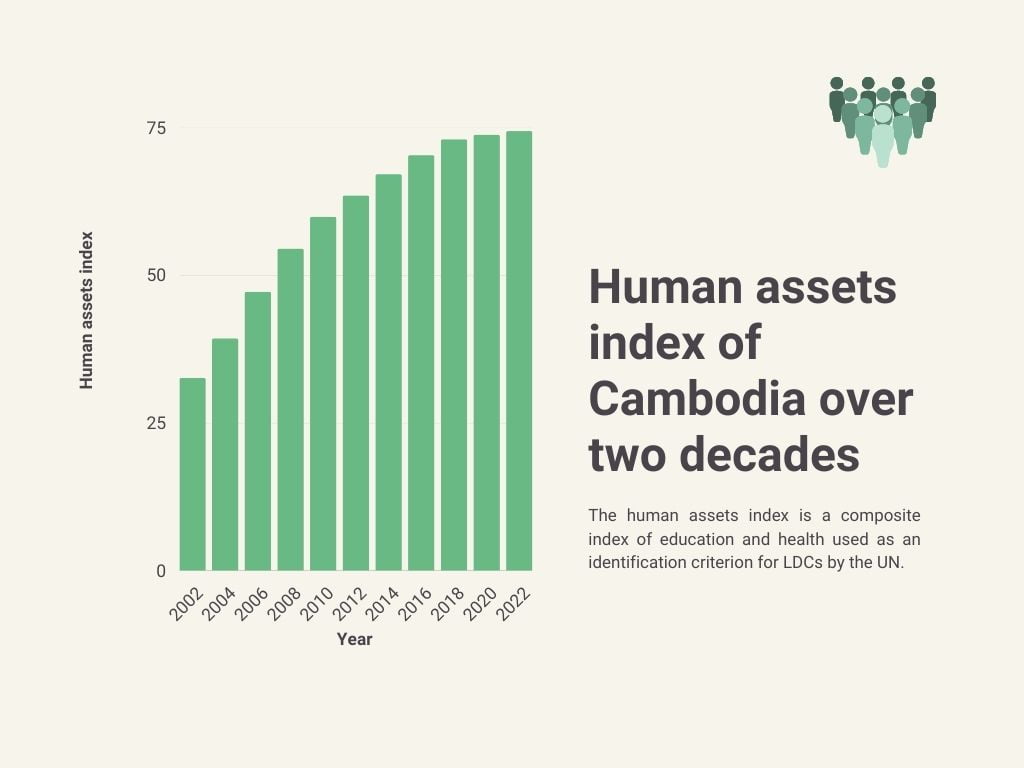

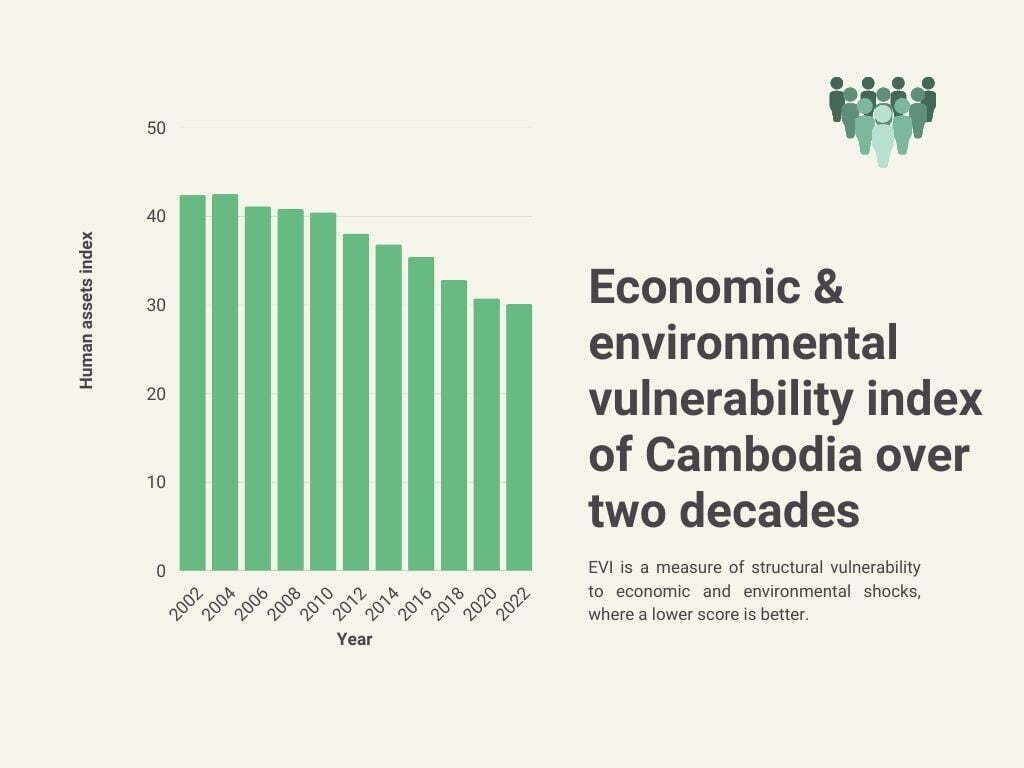

The UN takes into account a country’s gross national income per capita, human assets index score and economic vulnerability index score when assessing LDC status.

More specifically, GNI per capita provides information on the income status of a country’s people.

The HAI is a measure of level of human capital, or how skilled and experienced a population is. A country with a higher HAI will be more productive. The HAI threshold for LDC graduation is set at 66 and above, while to be included as an LDC a country must score 60 or below.

EVI is a measure of structural vulnerability to economic and environmental shocks. This measure considers the share of agriculture, forestry and fisheries in a country’s gross domestic product; instability of exports; a country’s geography; and the location of its population within its geography, among other factors.

Cambodia met the graduation criteria for the first time in 2021, according to ADB.

This means that the country could graduate in 2027, after going through another two triennial assessments conducted by the UN’s Committee for Development Policy.

Despite this being cause for celebration, it also presents challenges going ahead.

LDCs have exclusive access to certain international support measures, including in the areas of trade; financial and technical cooperation; and support for participation in international forums.

Cambodia has particularly made use of the trade-related support which comes with LDC status.

These trade benefits include preferential market access for goods; preferential market access for services & service suppliers; special treatment regarding obligations under World Trade Organisation rules; and technical assistance & capacity-building.

“Cambodia is one of the few least developed countries that has dramatically increased its exports to the European Union through preferential treatment and lenient rules of origin, allowing its products to enter Europe duty-free,” ADB said in an article posted end May.

Cambodia will slowly lose these privileges after it graduates from LDC.

This means that the Southeast Asian nation will need to ensure that its market access is not threatened.

To do this, Cambodia should work on expanding its free trade agreements, ADB said.

So far, the country is off to a decent start having inked two separate bilateral agreements with the China and the South Korea last year. Cambodia also participated in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership agreement.

RCEP is a free trade agreement among the Asia-Pacific nations, including Australia, China, Japan, South Korea, New Zealand.

Although this is a good start, ADB said that the country will should prioritise its market access in the EU and Japan.

In 2021, Cambodia’s exports to the EU came in at EUR3.5 billion, which then increased to EUR5.5 billion in 2022, according to the European Commission.

Meanwhile, exports to Japan in 2021 were USD1.7 billion, according to data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity.

Cambodia exported a total of USD27.3 billion worth of goods in 2021, according to the OEC. The country’s main export is textiles.

Although the onus will fall on Cambodia to ensure strong trading ties with other countries, there will likely be some support from its current partner countries as it transitions.

The UN has outlined a “smooth transition strategy” for countries graduating from LDC status. The strategy is meant to help a country stand without the supporting crutches which comes with LDC status.

The UN strategy includes recommendations to the LDC’s partner countries.

It states that partner countries “should support the implementation of the transition strategy” through the extension of existing differential treatment as well as preferential market access. These decisions are left up to the partner countries and would differ on a case-by-case basis.

There are other facets which Cambodia can capitalise on too, especially as world trade becomes more complex.

“The trade scenario is becoming increasingly complex, given the expansion of the trade agenda to new areas such as e-commerce and digital services,” ADB said.

There are many opportunities to use digitalisation to take advantage of wider cross-border market opportunities, ADB said.

This is what Association of Southeast Asian Nations is pushing for within its own economic community, of which Cambodia is a member.

ASEAN stands for Association of Southeast Asian Nations and is a political and economic union of 10 member states in Southeast Asia. Members include Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

ASEAN members in May adopted a declaration on advancing regional payment connectivity and promoting local currency transactions to drive synergies between member states.

Just recently, Malaysia and Indonesia have implemented a QR code payments system which allows direct transactions between the two nations’ currencies. This makes cross-border payments easier and cheaper.

Despite its ASEAN neighbours making progress, ADB noted that Cambodia faces some challenges in accessibility and human capital when it comes to digitalisation.

“Nevertheless, the lack of digital skills and affordability, which inhibit using digital tools and platforms, remain major obstacles limiting Cambodia’s digital trade prospects,” ADB said.